criticism is NOT dead 😤

An interview with *the icon* Philip Sherburne on the state of music, writing, Pitchfork, and criticism.

Want more interviews, essays, and reports on trends? Subscribe to The Trend Report™ for weekly dispatches ⚡️

What’s the point of criticism in a culture of constant ingestion? If I can stream whatever I want, autoplaying for the rest of my life from a queue of my non-making, morphing art into entertainment into consumption. The result is a landscape of devalued creative expressions and a devaluing of creatives. Why pay an artist when I can just lift this for free? Why seek out something good when the computer can tell me what I should do? Why invest in quality clothes when I can just zip this shit off SHEIN? There’s a really sunny darkness to these times, in that everything is too easy and audiences, people, are happy to coast, letting some algorithm and or artificial intelligence do the work of tasting for them. Export your own mouth! Just swallow and swallow and swallow: that’s the trap of “ease” we’ve all fallen into. This isn’t an indictment but our lived reality, a technoscape where something as sacred as Hollywood dies because we liked swiping too much. It’s neither here nor there: it just is.

This is why we will never build statues of critics in today’s world. Everyone's a critic, which means no one’s a critic: “I have social media, therefore I have an opinion worth sharing with everyone and no one.” That’s not inherently bad, but there is a bit of a loss when we think that there has always been a deluge of information — and key persons have always helped us wade through the waters, guiding us toward what is truly worthy of our time via added context that connects to our condition. Social media somehow confused criticism for gatekeeping when, in many ways, the critic is a gate-opener, a person whose job is to see and share. To think we went from Aristotle critiquing Plato to the New Yorker saying criticism is invalid because of Swifties. I’m confident we will see the days of the blogger, a genre of internet person who embodied criticism so well, reemerge as we get more and more tired and more and more bored of the technotainment landscape: we need trusted voices to help us understand what’s worth our time. We only have two eyes. Why not give them to a trusted source to preview what’s worth watching?

I have many people who I turn to for “this.” For American politics, it’s Jamelle Bouie. For men’s fashion, it’s Max Berlinger. For pop culture, it’s

. For movies, it’s David Ehrlich. For internet, it’s The Digital Fairy. It’s a melange of different people, some of whom dip into different cultures, all of whom seem to have a similar “vibe” to what I’m looking for in my life and likely what they’re looking for in their life. I didn’t always have this stable, as I was once more specific, having just a handful of people whose opinion I trusted implicitly for everything: these were the classic culture critic icons — the Robin Givhans, the Roger Eberts — followed by the current elder statespersons of criticism, like the Chris Blacks, the Tressie McMillan Cottoms, the .Following Roger Ebert (RIP, my sweet king.), the longest one of these cultural shepherds I’ve followed has been Philip. I think it was in the mid-to-late aughts, when a friend who was very into Resident Advisor told me that I needed to follow his writing, as he had such great taste when it came to the specific style of electronic and experimental music that we both liked. And the friend was right: I’ve found Philip’s taste to overlap with mine in ways that have shaped what I listen to and how I think about the music that I listen to. Although the music often isn’t, his writing — most notably for Pitchfork and in his newsletter,

— is effortless and warm, the kind of channeling you need to help understand media that is by nature more esoteric and “dense.” He’s the type of person you follow online and think, “Damn. They’re living the dream.” in that they’ve fused an interest and knowledge of the arts with being in constant pursuit of enjoying more and more of said artform. He has crafted a button of taste and continues to hit it again and again and again.Philip lives in Menorca and, after planning a visit there for my birthday in May, I figured I’d send him a note. Would he like to meet up and chat about music and criticism? His life and work at Pitchfork? The state of writing and the state of the world? To my surprise, he was down and, on an overcast Tuesday, I biked to his town and we met in a square where we sipped on little drinks and chatted a long chat before he had to return to his garden to work (and finish other writing and Balmat related things). It was a brilliant meeting of minds, the sort of meet-your-hero thing that happens and far exceeds the reality constructed in your mind. Always reach out to people you admire!

Thus, a meditation on music and criticism with Philip Sherburne and Kyle Raymond Fitzpatrick. Note that this interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

KRF: You’re always writing about music and always have great things to recommend. But, given your cadence of reviewing, writing, and sharing music every week, what sticks with you? What’s been sticking with you this year?

PS: I don't think there's any real through line yet. There's always an ambient baseline that I can put on anytime, especially while I'm editing or writing: I gravitate toward ambient music, to experimental soundscaping. I'm always looking for something unusual to grab my attention. Interesting songwriters are few and far between, as far as my taste goes, but Astrid Sonne this year I just adore. I liked her previous work a lot and I feel like she started singing and really writing songs and doing this kind of Tirzah-like thing, which I hadn't expected from her. I had that record in really, really heavy rotation. I'm still listening to the ML Buch, which is just such a strange and captivating album. I put it on just the other day. It's really good driving music.

KRF: Oh, I haven't listened to that while driving yet — but I’ve listened to it while doing literally anything else. I listen to it like every other day. I hesitate to say it’s “weird” but, like, it's just so, so surprising every time.

PS: It is weird. She has a song called “Flames Shards Goo.” That makes perfect sense! Flame shards goo? Yeah, that makes sense.

KRF: There’s something to her and Astrid: they’re sort of a new guard of artists. I’d add Nourished By Time too, these esoteric, really heady, almost literary musicians who are not necessarily who you would expect “songwriting” from. It's surprising in a nourishing way. I think that speaks to the state of music.

PS: They're not taking their cues primarily from indie rock which, ten years ago, you would have had Dan Bejar and Destroyer. That stuff's great but this is a younger generation and they're coming from different perspectives. And the sounds are more surprising too. There’s also the Jessica Pratt album: I'd never totally paid attention, as her albums are the kind of thing you would pull up on streaming while cooking or something. But this latest one I've really gotten into. I'm not a lyrical person, naturally, because I always gravitate toward production and the kind of the sound and feel of the music. I love that you can’t really tell if Jessica Pratt’s album was from fifty years ago or from today. It has this kind of spooky quality to it. Keeley Forsyth, who is a British actor who has been acting since she was a teenager, does this kind of haunted folk thing — like very spare organ and singing. She has a really powerful vibrato, very Scott Walker. Her new record I just reviewed and I really, really liked that it's not at all a summer record. It's so heavy and will sound twice as great come fall and winter. Then I really liked the Bullion album, which is just smart pop music. Have you heard it?

KRF: I have. I remember loving the last few EPs, finding them so charming and sweet but quick. This album seemed really quite lush, a really thoughtful evolution. And really smart to have a song with Carly Rae Jepsen, where she's sort of almost like a shadow within the song.

PS: Right? Like you see her in the credits and you're like, “Oh! Okay.”

KRF: And even Panda Bear, which was really interesting because it almost sounds like a mirror: I can't tell who is singing. I never would have put his voice with Panda Bear but it’s a perfect match.

PS: At first I was like, “Why are they leading the album with a Panda Bear song? What a weird, self-undercutting move.” — and then it made sense. I find that album really charming. I've been playing on repeat to the extent that my daughter is like, “Papi! Not Bullion again!”

KRF: That's hysterical.

PS: That's some of what I've been listening to.

KRF: That's a good collection — and they definitely all fit into a world. It’s funny because you have a specific beat and it’s so rare now that publications have writers with beats. Having done a beat at one point or another, it can get a little fatiguing or, like, boring. How does the need for a publication to have someone who's covering a specific genre — Say, electronic, say ambient. — influence personal taste? Does it matter? Is there a universe where you have to review a Marshmello album?

PS: When I was coming up, I wrote more narrowly about dance music, although I listened to other things. I wrote mostly about certain strains of techno and house, experimental music for The Wire, things for Resident Advisor. I kind of became known for that, which was probably good, because there weren't a lot of other people covering that zone. When Spin asked me if I wanted to be a contributing editor, to ramp up their electronic language as the whole EDM thing kicked off, I kind of fell into writing about my weird music nobody cares about and also writing about EDM, really commercial stuff. When I went to Pitchfork, I continued being asked to write about electronic music, generally speaking, but I think they let me — and encouraged me — to branch out more. These days, maybe there's less need for somebody with a specific beat. Look at somebody like Kieran Press-Reynolds. Kieran's work is really laser focused, like internet rap, TikTokcore, and all these things that, as a Gen X, I have no idea about. Kieran writes really, really well and I think it's good to have somebody who has that beat because they're able to translate really niche internet cultures to a broader audience. It's always a balance because there's the stuff that I get asked to do — like fall on the sword and review The Chainsmokers. These things happen and I do it willingly. Sometimes I enjoy it! Sometimes I don't. I have a really hard time writing negative reviews. There are people who are really good at it, but I'm not.

KRF: It's interesting. It reminds me of a lot of young writers, performers, and artist types in their twenties who don't put anything out there — because they don’t want people to judge it. Like. I get that. But also you're not gonna make anything then: if you're too worried about being critiqued or being laughed at or whatever, you’ll be lucky enough to live. To be critiqued is a sign that you're doing something. It’s funny, because you’re both a critic but also put out music, under Balmat. How do you navigate running a label with writing about music? It’s an expression of larger taste, but very different expressions of said taste.

PS: They definitely run in parallel. I mean, I wrote about Shy Layers years ago and became a real fan of his work — and then I ended up putting out Anagrams, which is a project he was involved in. I reviewed Panoram a couple years ago, and now we're putting out a new Panoram. I definitely don't want there to be a pipeline of Pitchfork reviews to Balmat releases but, at the same time, if somebody sends me a demo and it's phenomenal — I'm gonna put it out. It just means that the pool of things I can actually review starts shrinking.

KRF: That’s interesting, given the state of “the industry” as far as both music and journalism and the shrinking of these spaces, especially writers. People look to writers — whether it's a music writer or politics writer — for some sort of help understanding the world and, when publications shut down, you’re losing an outlet for information. There will always be more outlets to do your writing yourself, like

, but we lose something. What do you think?PS: I have an unbalanced negative view, shot through with a lot of fear. Take my perspective with a grain of salt but…look at what's happened with Pitchfork — and that’s just one example of a much larger industry-wide decimation. Yes, Pitchfork did lots of stupid shit, yes, it occasionally published a clunker but Pitchfork was a really big group of diverse, talented people all working together, building a repository of knowledge and experience. And they kind of…just destroyed that in a day. There's still good people left there. I love the people that I work with! I think we're doing the best that we can because we don't know any other way to do it, because we want to honor the legacy of the place. We still believe in the work. But there's no denying that there is going to be a before and after: you're gonna look back ten years from now and it's gonna be like looking at a tree, where you cut into it to look at the rings—and you can tell where a forest fire was. There's going to be a black ring for 2024. It's happening across the board. There is this movement toward independent writers and independent voices and Substacks and things like that — and I think that's good. I'm thrilled that I get to do it. I'm thrilled that people are willing to pay some money for it! I have readers, I have experience. Younger writers don’t have that. I don't know how sustainable something like Substack is going to be. Maybe we bundle subscriptions? Maybe we reinvent the magazine? But the problem is the magazine business model, at the moment, just doesn't work. Or private equity sucked all of the money out of the industry? It’s various things. It's super difficult. The day the Pitchfork layoffs went down, I just happened to see on Instagram post that my wine store was hiring a delivery driver and, for about eight magic hours that day, I was like, “Fuck it. I'll deliver wine around the island and listen to weird music — and I'll blog about it at night.” Then reality set in but, for a moment, I thought change was possible.

KRF: It’s all for better and worse. I don't think it's just writers or the publishing industry: it’s everything. It’s the fall of Hollywood, which is so shocking to me. I really don't think people understand it. But there are only so many ways you can do these things, do what we do. You could start sharing videos reading a review or something — but it’s the same thing, just in a different form. I do think all this is a sort of growing pain, that we’re experiencing the limits, that maybe we went too far and are coming back. That’s what makes it interesting: it’s not just writing.

PS: It’s anyone in the middle and working class.

KRF: Absolutely. When I think about Hollywood — which I think about a lot — I wonder what the vacuum of an industry town’s collapse will create. What will people dream of doing? Are they going into video games? Will they dream of being architects? AI prompters? It’s really fascinating and I don't think there's been enough thought about the vacuum that’s being created. Even the “authority” of publications is being sucked up too. Criticism is a hot subject because, when I was growing up, I used Pitchfork to understand what to buy and what to listen to. It’s a trusted source. Now I go on TikTok or directly to Apple Music along with Pitchfork and Resident Advisor and Bandcamp and all these other places. But, for so much of the audience, for consumers, they’re not actually buying anything: they’re just easily accessing everything via multiple information streams. That’s the context for all this: real people — and fucking stans, who will follow anything. It’s an interesting overlap.

PS: They are the people that want to know if the new Taylor Swift is good or not — and they no longer need criticism because they can go to Spotify and or TikTok, or wherever, and figure it out for themselves, right? Or figure it out very quickly. Then you have people that want discovery: they don’t seek criticism in the same way I needed Spin when I was a teenager. Now you can go to the homepage of Spotify, you can follow a bunch of people on Bandcamp: there are a million places. Just follow a bunch of record labels and DJs on social media. That said, I do think it's so overwhelming: there's so much information and there’s a role for tastemakers. It’s a terrible word but, for curation, for certain people who have a certain disposition, there's still value in having places like Pitchfork or The Quietus or Aquarium Drunkard or NTS, where you can find new music that you're interested in. If category one is buyers who use consumer guides, category two is all about discovery — and category three are people who believe in criticism as an art form, as entertainment in itself, who want to engage with the writer. There will always be people who are like that. It's just that there's not very many of us, and I think it's hard to sustain a business model for us. There are still readers but somebody has to figure out how to make it work.

KRF: I feel the same way. There's so much music in this present moment, but also there is so much music being built on top of. There is more opportunity to go beyond time, which happens in social media regularly, particularly on TikTok, which exists in nonlinear time. Let's use Kate Bush as the example which, yes, Stranger Things, but that doesn’t necessarily exist in a silo. In the younger mind — or in a lot of our minds — now isn’t a constant but the archive is. Every generation does this “return to the sources,” to find and log history. This gets at something like an almost communal criticism, which already happens on spaces like TikTok and Instagram, where you can go on Live the night of the Taylor album with two fandom leaders who act as culture critics. It can feel like a mini-salon around music and the arts, which is cool — but isn’t that just reinventing podcasting then? I don't think people listen to podcasts as much as they used to but I think people do listen to ideas being exchanged in any form.

PS: I love the idea of podcasts, but I just never have time.

KRF: I'd rather listen to the music.

PS: I like

for example, because it's a podcast but they give you the transcript too.KRF: And, somehow, that reinvents writing, which is somehow preferable? I don’t know. What’s next for you? What do you think is next for music? What's on the horizon?

PS: In the immediate future is to keep on doing what I'm doing. I'm really enjoying the newsletter and I'm trying to interview more people, with a couple coming up. I'm still at Pitchfork. I'm still doing that until my contract is up in November — and I hope that they want to keep me on. And I’m working in my garden.

KRF: And Balmat?

PS: We've got the Panoram album and another announcement after that. [NOTE: This was the recent Bartosz Kruczyński release.] That's going to be a really nice one: it's a sort of diversion that’s ambient adjacent. The releases are getting more and more “adjacent,” like we're kind of coming back to an ambient sweet spot. I need to listen to some demos too since we have demos piling up.

KRF: Balmat is so specific. I can’t imagine things are that off as far as demos. Or are they?

PS: Some. I got a Brazilian phonk song about Lionel Messi. I was like, “I don't need that.”

KRF: Now that’s what I call music. Do you get a lot of people reaching out for reviews?

PS: I get music from publicists and I get music from labels, everything from Skrillex to, you know, some guy in Bratislava. I get them from individual artists, some of whom I'm familiar with their work and some of them just find me on Squarespace and write. I try to listen to as much as I can and some of that turns into reviews every now and then. Sometimes something I buy will turn into a review, not as much on Pitchfork but it's definitely happened in the newsletter. For the newsletter, I try to keep it a PR-free zone although that's not really feasible. I have a massive spreadsheet that I've been running for years, of everything that crosses my desk. I log it, with a release date, so I know what's coming out.

KRF: Wow.

PS: I need it to pitch reviews. The newsletter has become really helpful for this, especially since it's weekly. I'm also subscribed to a million Bandcamp emails because I buy a lot of music on Bandcamp. Anytime anything vaguely interesting crosses my desk, I put it in the spreadsheet, so I can be like, “Okay. It's May 13 and a new issue is going out. What's new this week?” It's a very quick way of sorting through stuff.

KRF: This is something I think about a lot, but I like to think you’ve launched the careers of a few people. I think about the feature you did on Rosalía way back when as a ground zero moment, when something big shifted.

PS: She was already big — and I honestly think that would have happened even without that story. It was a right place, right time thing and actually Ryan Dombal, my editor, who was really aware of her stuff. I was aware of her but I hadn't been following her closely. I feel really fortunate, but she’s got her own momentum. She has had no problem making it on her own. Marina Herlop…a little bit but, again, all of these people have their momentum.

KRF: It helps though. A big drop in the bucket!

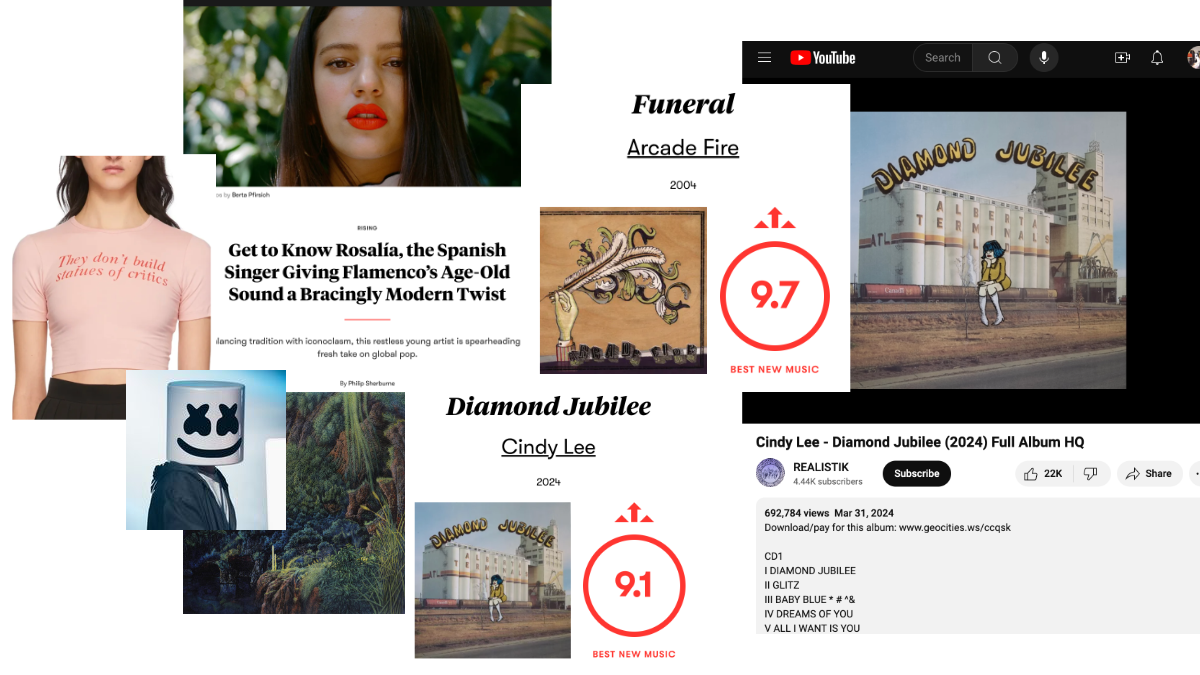

PS: Maybe it helps them get another couple of gigs here and there, and then that helps this snowball effect. I can't think of ever doing anything that was like what Pitchfork supposedly did with Arcade Fire. That was a band they plucked from obscurity, gave a perfect 10, and then became the biggest indie band of their era.

KRF: That is true. Does that era exist anymore on Pitchfork? I think it happens in more independent spaces, in a newsletter or TikTok — but that is true. I remember the time when there would be a Pitchfork review and then that was all anyone listened to.

PS: I wonder about Cindy Lee. But again, the Cindy Lee album I feel like is more of the collective consciousness. Yeah, Pitchfork wrote a phenomenal review, it’s Best New Music and all this stuff but, before that review — certainly on my timeline — everybody was talking about it on Twitter. Everybody was talking about it in my group chat! So I don't know. I guess it's an interesting question. How much influence does that Pitchfork review have? Or any one particular review? They can still move the needle a little bit.

KRF: I think it does. It relates to all the stuff we talked about, that there are certain people who look to certain people to sort out culture, to get a vote of authority. That’s tastemaking, qualifying stuff. I think that’s what happened with the Cindy Lee thing because, you’re right, the review wasn’t what broke it but it opened the floodgate, to analyze the performance of Cindy Lee and the album itself, to shift from music to “Oh this was uploaded directly to YouTube.” and “This feels so old school but not!” Then people were going to shows and writing 10,000 words on them.

PS: What I think is so funny with the Cindy Lee thing is I'm sure that the whole Geocities page, the PayPal, the RapidFire link…I don't think any of that was premeditated. I don't think it was like, “We're gonna get more press if we do it like this.” It was just an easy way to get it out there, without paying Bandcamp. I'm convinced that, had they just put it up on Bandcamp, maybe Spotify, no one would have given a shit. You know what I mean? It would have disappeared. But, at the same time, if another band did the same thing tomorrow…it wouldn't have the same impact. It's like when Radiohead did the pay-what-you-wish album. It made a huge splash, coming out of nowhere with this novel proposition.

KRF: It’s very much a medium is the message thing that hit at the right time, when so many things were collapsing, offering a new or not-new way of doing things. Is it really that new? I don’t think so — but is it a rethinking of the tools that everyone has access to? Done in an interesting way? Yes.

PS: In a way I think that felt true to them and to the music.

KRF: Absolutely.

PS: Very “I don't give a fuck: here's the music.” thing and that connected.

KRF: In that regard, you very infrequently have high-quality authenticity that hits at the right moment, in the right way, where it does break through. I didn’t listen to the Jessica Pratt album because it's so easy to access — but the Cindy Lee album? I went and ripped it off of YouTube because I had to work for it. It was like a psychology experiment with mice.

PS: That’s funny, because you know you actually could have gotten it for free from the link.

KRF: I mean…absolutely I made it harder!

PS: You’re like, “I’m still stealing it — but I’ll work for it!”

KRF: That was exactly my thought process.

PS: I downloaded it because I was like “30 bucks? That's a lot.” Then I downloaded it and realized it was great and that it was 30 Canadian dollars then, fuck it, I PayPal’d. It’s really funny. I'd love to know how much they made on that. I would really love to know how many people paid for it.

KRF: I really don't think that much.

PS: Maybe yes? But I don’t know.

KRF: I don't know, but I do think that they're gonna get more shows. Obviously, it's already happening. I don’t think we’ll see the biggest impact until the end of the year, when it's the best album and the big thing of the year and everyone is like, “Oh right: Cindy Lee.”

PS: They canceled their tour. I don't know what happened there: they were out on tour and they canceled. I don't even think they publicized a reason.

KRF: They definitely seem like an artist of mystique.

PS: Or they really don't want that kind of spotlight.

KRF: Which again…plays into it! They’re doing everything right!

PS: Next they’ll be opening for Lana Del Rey.

For more from Philip, be sure to subscribe to his Substack and follow him on Twitter.

The foreword is so good. People I admire include: you

Category 3 over here. What a great discussion, thanks!