🧱 A Word With: Architect Omar Miranda

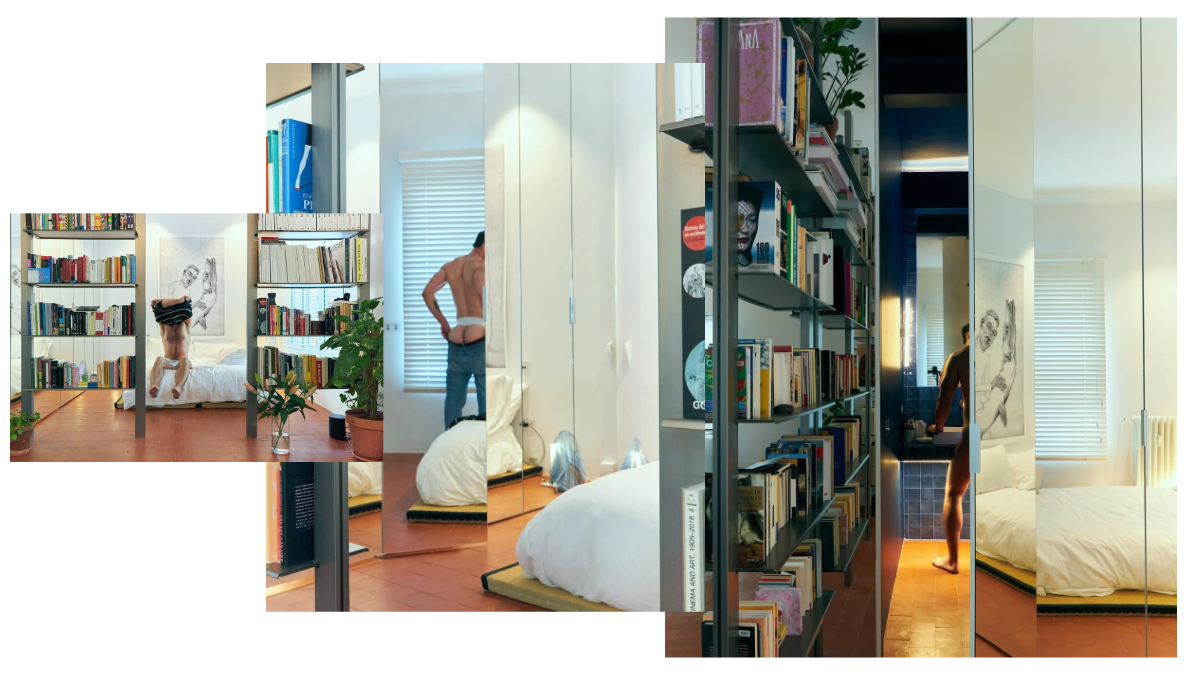

A chat with the Cuban architect and designer on the influence of queerness and sensuality on creating interiors.

Explore more coverage of Madrid art and culture here. Subscribe for more trend dispatches, about life online and off ⬇️

I came across Omar Miranda’s work via his work with Sudor, a collection of lamps that are obviously quite appealing. Sleek in structure, each item is a vessel for draping intimate apparel on, making it appear as if the light fixture were taking off its clothes, that it was watching the intimacies before it from the bedside table and wanted to join in. It’s clever and cute while, obviously, being quite a sexy work. It reminds of Vinçon’s Bolsa lamp by Victor Juan Arrufat: a fun-and-functional object that reflects the body, that makes use of our ephemera.

In visiting Madrid, I wanted to meet with Omar to talk about these cool lamps — but to also hear about his architecture work given that, like the lamps, they have a very specific queer sensibility that one doesn’t often see in architecture. I was curious about his approach to these creations as I hadn’t quite made the connection between queerness and the creation of architectural spaces. Why aren’t buildings more queer? And how could one make them more queer? On a rainy Monday, Omar and I met up at a coffee shop to chat about influences, the body as inspiration, and the importance of community.

KRF: One thing I really love about your work — both in terms of spaces and as far as object design — is you can feel the influence of, say, the elegance of the 1980s, this idea of an opulent life. That’s very nostalgic for me because I remember growing up in the nineties and feeling like that’s what it meant to be a really cool adult. You pull it off so well, which seems right on time given how everything from glass blocks to wide suiting is making a comeback. How did you get into that aesthetic? Does the city play a role in this influence?

OM: I grew up in Cuba, also in the 90s. Growing up in Cuba was like growing up in a very peculiar relationship with time, like inhabiting the past, and I think that is a great influence. I was influenced by all the Cuban design of the 80s, the art, the ceramics, the tiles: I think about that a lot. I love it, in Spain, you can see a lot of works of art in buildings, in cities like Oviedo, for example, you can walk many blocks and see all the art murals that inhabit the architecture. I love that kind of aesthetic. Also in my time as a student I was influenced by many architects who developed their practice in the 80s like John Hejduk or Aldo Rossi. Also all the interiors from the second half of the 20th century that Pol B Preciado, for example, analyzes in Pornotopia as an architectural and media project.

KRF: That’s one thing about Spain: craftsmanship — and artisanal craft, like tile making — is so huge. From the outside, you don't think of it as being such “a part of the culture” but it is.

OM: Spain has a deep-rooted tradition in construction and craftsmanship. It is true that it has a deep ceramic tradition that I am very attached to. For me, it is important to make special things for each space, like art nouveau, when the processes are no longer so industrial. It is important to think of the construction material as if it were part of a sculpture.

KRF: I've met a lot of architects and I know a lot of architects and I don't think many of them approach space as a sculpture, which is a really elegant way to think of space. Yes, there is the actual structure that is permanent — but spaces are always changing and are a bit like clay. Even permanent things change. You have to live there! So it changes with you. That’s the beauty of living.

OM: I don't know why but — for me — sculpture has always been in the center, both as friends and my community. I don’t have many relationships with other architects. My small circle are all sculptors and, for me, it's important because sculpture thinks about material and the body in a different way than architecture.

KRF: Do you make the tiles that you use? I’m assuming you source them and help select glazes.

OM: No, the process is really difficult and expensive — but maybe in the future. I want to do more baroque architecture. The thing about architecture and interior design is that it’s really expensive. It’s easier and more enjoyable to do other objects and furniture because you can build it in other ways.

KRF: I mean, there’s more of an overlap and similar tools between making a table or lamp versus learning how to do ceramics. Which brings us to Sudor, where the lamp designs are bring together so many ideas so well of sensuality and the body. It makes the lamp-as-object a lot of life, which again plays into the eighties luxury. They’re so beautiful.

OM: We wanted the lamp to be a very sexy object, one that spoke about sensuality, about the body, about fluids, but with a very elegant aesthetic that countered this sexual and corporal discourse, so it reminded us of a lot of advertising from the eighties, perfectly chromed surfaces, light and dark backgrounds, we had a lot of references to advertising objects from commercial magazines of those years. Also, both Rubén and I greatly admire designers like Oscar Tusquets who have this kind of language.

KRF: I think you achieved that. How did you meet Ruben? Where did the idea for Sudor come from?

OM: Ruben and I met many years ago on a dance floor, where I know most of my friends. Ruben comes from the world of fashion and I from a more artistic practice and architecture, and we felt that we had to do something together. The idea came up in a conversation about gestures related to lighting environments, the gesture of putting a handkerchief over a lamp to filter its light and the idea of sensuality. You come home from the club, at night, you get naked, you are about to fuck someone and when you throw your underwear it falls on the lamp and creates the perfect atmosphere for that moment.

KRF: There’s this idea of movement, literally throwing something, which I hadn’t thought about but is so clear. These lamps capture a moment in very specific intimate time.

OM: For me, the movement of the body is at the center of all the stuff that I think about. Dance is really important! It’s everything for me and I think about creating architecture for movement, for the body. Do you know — I don’t know how to say in English. You know tejas? On the roof of the building?

Omar points upward, to roofs, then out the window to the roof of a nearby building.

KRF: Yes, I think so.

OM: They’re made from this part of the body —

Omar pantomimes wrapping something across the thigh, using the thigh as a mold.

KRF: I didn’t realize that but it’s so obvious now.

OM: It’s so obvious, no? I have the fantasy to create more elements from the body and from its movements.

KRF: The way that you do it is so refined because I have seen so many bad versions of this idea, where it’s a literal torso made into a lamp. It’s hard to pull off and you’ve been able to do that.

OM: The lamp is part of the body because the clothes are designed and created under the mold of the body, this underwear is the perimeter of a pelvis as a shirt is the perimeter of the torso and arms, the body subtracted.

KRF: Like a light in your pants, the penis or vagina or whatever you have in there.

OM: Yes. When I have fashion commissions, for example accessories, I think the same thing. It has to do with how you move and touch your body. I extract those movements. How you make your body feel comfortable, how you embrace other bodies: those pieces come from there.

KRF: Having that human element in architecture and design is so important because we live with all these things, which gets at the idea of moving through space, of dancing. Architecture and design isn’t always “human” but we use space and objects to express the human like cooking and playing games and having sex: all things you do in a space. How does dance (or the culture of dancing) play into this?

OM: For me, dancing is one of the most important things in my life: it is the only moment when your body moves without the idea of productivity, it is anti-capitalist. You don’t produce anything! You just enjoy the moment, you embrace, you feel, you communicate. When I grew up in Cuba, dancing was everything. People always interact on the dance floor! I remember my parents dancing a lot and I grew up suspended between their chests while they embraced each other dancing salsa. Both in the years I have been in Madrid and in the seasons I have spent in Berlin, I have danced a lot and thought a lot about the idea of movement. It is a way of experimenting, of becoming aware of your body, your reality and interacting with people, of speaking without speaking.

KRF: I mean, Berlin has a history of exactly that.

OM: I remember being 23 or 24 years old one summer in Berlin and dancing non-stop to dark techno, but I was really dancing salsa. I would spend the whole night dancing salsa, Cuban dance, but the music was techno. At that moment, I really understood that dance is universal: move however you want, your body is finding its own language..

KRF: There’s no right or wrong way to do it with techno. It’s not something I think about when I go to shows, neither how I move or how other moves: it’s not specific.

OM: Salsa is more strict movements. I’ve been thinking a lot about — because I read a lot about — how in Africa, in the Caribbean, and in Brazil, dance is a kind of language. You interpret the drums and you can communicate with other people to tell stories.

KRF: And then you’re translating that to architecture. Another thing that fits into this as far as an influence that I feel is worth mentioning: queerness. That feels very present in your work and you do it with such an elegance, again. There are no rainbow tiles but instead the representation of life. How does that inform your work?

OM: It’s really queer. All the people I have around me and the way that you think about architecure, interiors, furniture, or design: I don't think about that in housing for a regular family. My clients are all gay or lesbian friends! The necessities are really different. The way you live your life is really different too. All the spaces are created for other kinds of life — and the objects too. We all have masculine and feminine energy and we can express this energy in your life in different ways. Sometimes you have more one than the other. Your space and your atmosphere has to embrace this energy.

KRF: This is a big question but why don’t you think architecture is more queer? There’s something so straight man about architecture — which I know isn’t true. All architects aren’t straight men. There are lots of women and queer people and persons of all backgrounds. But, when I think of a house, I think of a “normal” straight family. But an apartment? Queer people. Why is that?

OM:It's about power. It's about power and money, architecture in general requires a very large material effort, great architecture, great buildings and infrastructures like airports, museums and other large buildings come from places of power and a lot of money controlled by white, heterosexual men.

KRF: So much of queer community is about bringing people together, to create safe spaces and to accommodate different ways of being and different types of people.

OM: I really want to, at some point in my life, think about how to live together in community. In Madrid, take a big space and make common spaces and individual spaces: it’s one of my architecture dreams, to build spaces for community. You need time. It’s not the job of one person. It’s the job of a group.

KRF: And, to the point of power and money, generally — and I don’t know about Spain, specifically — queer people don’t have the most money or power. To express something like you’re talking about, it takes a lot more planning and time and effort because it can’t be right now. If that is the case, it’s probably older queer people. We all have to work now. We don’t have that liberty to be able to pursue that. Speaking for myself, I want — and I feel like I know a lot of people who want — to always be in community, in a world, interacting with a larger city or with others who think similarly. It’s hard.

OM: The most important thing is to have the idea and to do it step-by-step. The problem is capitalism and that we are really individualist: you don’t think about community.

KRF: And it’s hard enough to meet people. Even for me, being in Spain for three years this summer, it took nearly that long to actually make friends. For two years, I wanted to jump into traffic. It was depressing as shit.

OM: That’s normal moving to a new city. In Madrid, I came here for school and spent five years here before feeling that. I have been here for twelve.

KRF: We’re constantly trying to figure it out, if it exists here or somewhere else. Where do we go?

OM: Me too. When I finished university, I thought a lot about Barcelona or Berlin but, at the end, I decided to stay here. It was a good decision because I really enjoyed being part of the city.

KRF: It’s hard wherever you are, which is also why I’m doing interviews like these. To try to meet more people. We’ll figure it out. What’s next for you, both for architecture and for projects? What are you excited about?

OM: Try to do more architecture because that’s the thing that makes the most money. The other projects are more like hobbies: they give money, but not for survival. Architecture is the work.

KRF: It’s similar to being a writer. You have to put things out in the world to get anything back.

OM: Yes. We want to continue Sudor too but with more furniture now. We’re thinking about chairs, a chair collection. We’re working on that now and, for me, maybe some leather accessories or jewelry.

KRF: Your table is just you, right?

OM: Yes, I did that through my studio because I needed furniture at my place and I designed three pieces and they’re not functional because it’s more sculpture. People tell me “What if you have a pet?”: sorry, guys. I don’t do that.

KRF: I thought the same thing and then — it’s not for me. Laughs.

OM: It’s for me, yes. I make it all through contacts from construction, in architecture, who can do many things and build other stuff — like the lamp too. We produce it in a factory in Valencia, which we’ll use for the second edition.

KRF: When will the second edition come out?

OM: Next month, I think.

KRF: That’s soon!

OM:It's the same lamp. The first one was made here in Madrid, in a small workshop. We wanted to make a more industrial production. The structure will be the same and the clothes can be changed. We made many lamps, with the red thong and the white panties, we also want to try to sell some special edition clothes made by people who interest us and represent the ideas of the project. And we would like to give more visibility to other items of clothing such as the shirt, scarves and other items of clothing.

KRF: Uh. Yes? Yes.

OM: And stockings too.

Explore more of Omar Miranda’s work on Instagram and learn more about Sudor here.